At first glance, dolmens and churches seem to have little in common. Dolmens are burial chambers from the Stone Age, while churches are places of gathering in Christianity. Nevertheless, it can be argued that churches evolved from dolmens, through the influence of the Romans. How this occurred is discussed here (see also from page 596 Megaliths).

Dolmens in Havelte

A dolmen is generally constructed from large stones, megaliths, which form a chamber together. Important ancestors were interred in such dolmens, as it was believed that the dead continued to live on. Often, the chamber had a passageway overlooking the fields or the settlement where the descendants lived. Sometimes, the descendants offered sacrifices at the grave, placing a cup with grain, meat, or milk at the entrance. In this way, ancestors were honored, and perhaps favors were also sought. The construction and rituals promoted unity within the settlement.

Two examples of dolmens can be found in Havelte, Netherlands (see also Megaliths pages 7-8 and Mythical Stones Part 1). There are two dolmens within sight of each other. Both monuments have a passageway roughly facing southwest. The passageway leads to a large chamber, enclosed within a mound. Often, such a burial mound was adorned with a façade, a forecourt, and a stone circle.

Periodically, a deceased person was interred. Fragments of hundreds of pots (photo: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden) suggest that it might have been hundreds of individuals, but it is more likely that only the elite were interred in these chambers, with the 'ordinary' people buried in pits nearby. As seen in some cemeteries today: a mausoleum for the rich and influential, a flat grave for others. The passageway allowed seeking advice from ancestors. The offerings placed at the entrance were meant to compel a favor. Sometimes, the bones themselves were used for rituals, bringing the dead visibly back to life. Thus, dolmens served as places of gathering for the community.

Although the dolmens in Havelte were built around 3300 BCE, one could view a dolmen as a precursor to contemporary churches. The megalithism responsible for dolmen construction in Northern Europe ended around 2500 BCE due to the rise of the Bell Beaker culture. With the arrival of steppe people from the east, the skill of building megalithic monuments in Western Europe was lost. While small stone cists continued to be made, the impressive structures that required specific knowledge were no longer erected in Western Europe (see also from page 596 Megaliths).

Continuation in Southern Europe

However, the steppe people had much less influence in Southeast Europe. In Sardinia and Majorca, the development of megalithic structures persisted. Tomba di giganti, nuraghes, and talayots were erected there. The Minoan civilization, centered on Crete, also refined the art of building with large stones.

For example, the burial chamber of Kyparissia Peristeria (photo: Giannis Seloulis) consists of four vaulted tombs built on a hill, next to the remains of a palace and residences. The tombs had beehive-shaped chambers where rich grave offerings were uncovered beneath the floor. The golden vessels and jewelry date back to the 16th-15th century BCE.

Ultimately, the Greeks and Romans built impressive temples for their gods. These megalithic structures were executed with divine precision. There are numerous examples, but Olympia is probably the most beautiful one. Olympia was dedicated to Zeus (photo: Annatsach). Over time, the surrounding area was filled with numerous temples, altars, statues, and eventually a stadium. The only permanent residents were priests and temple staff. The oldest temple (built around 600 BCE) was dedicated to Hera, initially with wooden columns later replaced by stone columns. The main temple was the Temple of Zeus, completed in 456 BCE. Inside was a 12-meter-high statue of Zeus on his throne, made of gold and ivory. It was one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. Walking among these impressive structures, you realize that megalithism in Southern Europe continued to develop unhindered into grand temples and buildings.

The Romans were also masters of building with large blocks. They reintroduced megalithism, in an advanced stage, back to Europe. One of the many examples is the temple in Vienne, France, dedicated to Emperor Augustus. It was built during the emperor's lifetime, before the turn of the millennium. Later, the temple was used as a church.

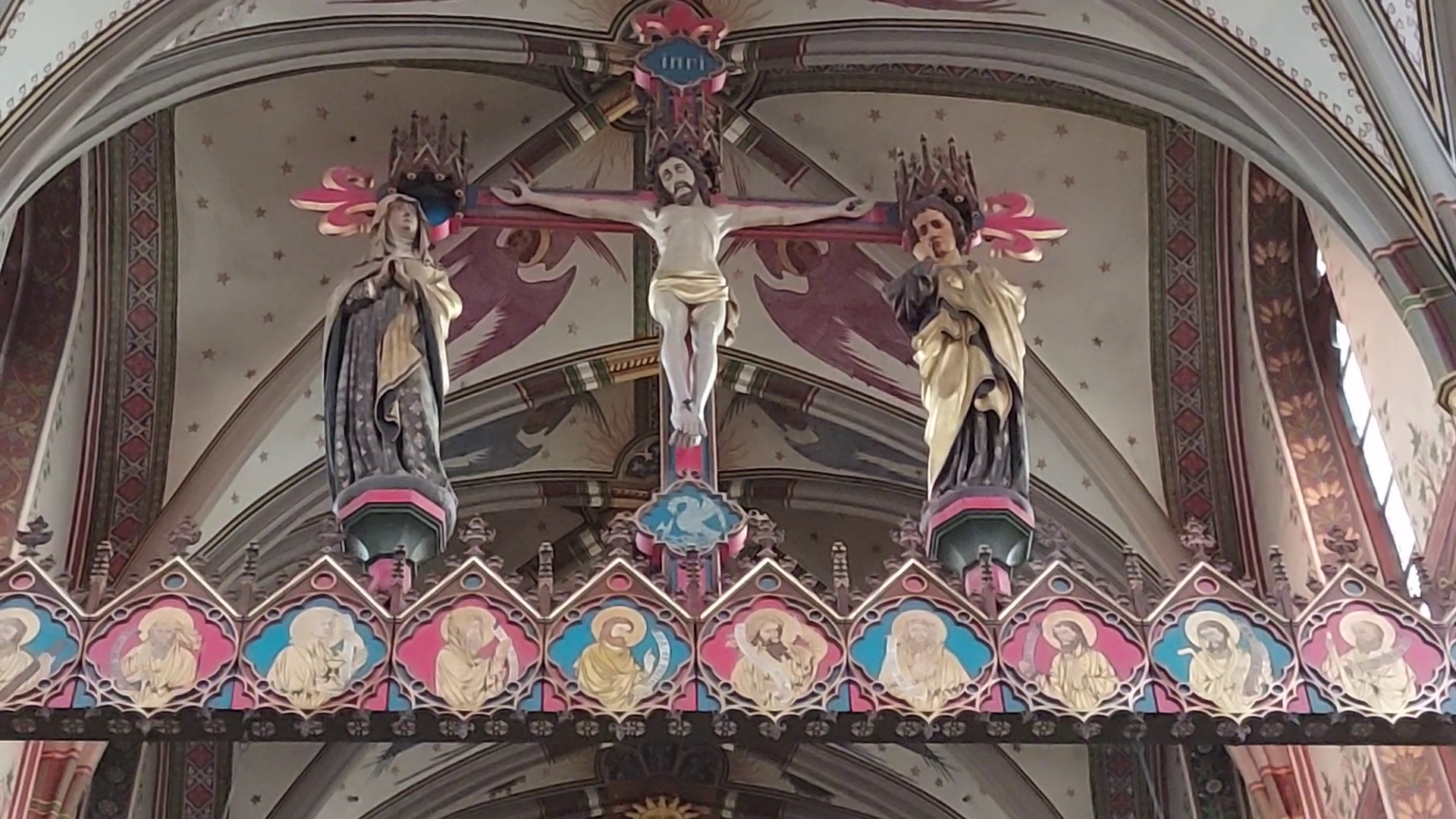

At some point, this thousands-of-years-old megalithism, via the Romans, collided with the Jewish culture, which also had roots dating back thousands of years. The Jewish culture had stories recorded in the Tanakh, stories that were passed down in synagogues. In the clash of these cultures, a new culture and religion emerged, as had happened many times before. The messianic belief from Judaism mixed with the Roman soldiers' Mithraism, giving rise to Christianity. Megalithism evolved further towards cathedrals. Hundreds of years later, these cathedrals flooded Europe during the spread of Roman Catholicism. Enormous churches were built, complete with forecourts, courtyards, menhirs (towers), and veneration of a deceased hero hanging on a cross. The hero who became God and rose again after three days from a stone grave with the capstone rolled away. The bodies of important community members were buried under the floor or in a tomb beneath the 'House of God,' also awaiting resurrection. A resurrection, much like the one that occurs each year in the fields as new life sprouts from the dead ears of grain.

Revival in Roman Catholic Churches

Ordinary people were interred in flat graves around the sanctuary. Priests conducted rituals, using beautiful cups from which the people drank during a ritual feast. All this was done under the watchful eyes of the saintly statues, each carrying their attributes. It is not coincidental that many Roman Catholic churches have a forecourt with a façade leading to the space with the graves of prominent individuals from the past. This architectural principle existed even in the late Stone Age.

The similarities with Irish court tombs and the tomba di giganti in Sardinia are remarkable. Apparently, the symbolism of the menhir, the forecourt, and the stone chamber remained imprinted in the collective memory. With the arrival of Christianity in Europe, that symbolism came back to life. Nowhere in the Bible is it written that people should build churches and bury their dead in them. The grand cathedrals with the deceased ancestors inside were indirectly a continuation of megalithism that began around 5000 BCE in Europe. After thousands of years, megalithism was back in full swing!

Reacties

Note: HTML is not translated!