One of the attractive aspects of archaeology is that sometimes you are allowed to let your imagination run wild to find explanations for extraordinary discoveries. It is also the biggest drawback, as you run the risk of your ideas no longer aligning with the facts. At the beginning of my journey along the megaliths of Europe in 2016, I suggested to Daan Raemaekers that collar-necked bottles could serve as oil lamps. Put oil and a wick in them, and they burn well. The professor pointed out that there should still be carbon at the edges. It wasn't there. End of imagination. In late 2022, Juan J. Negro et al. published an article (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-23530-0, also see https://archeologieonline.nl/nieuws/nieuw-onderzoek-heilige-uilen-blijken-prehistorisch-speelgoed) stating that the Portuguese plaquettes from the Stone Age were actually children's toys. Is this perhaps another oil lamp story?

Painting owl

Painting owl Photo Hendrik Gommer

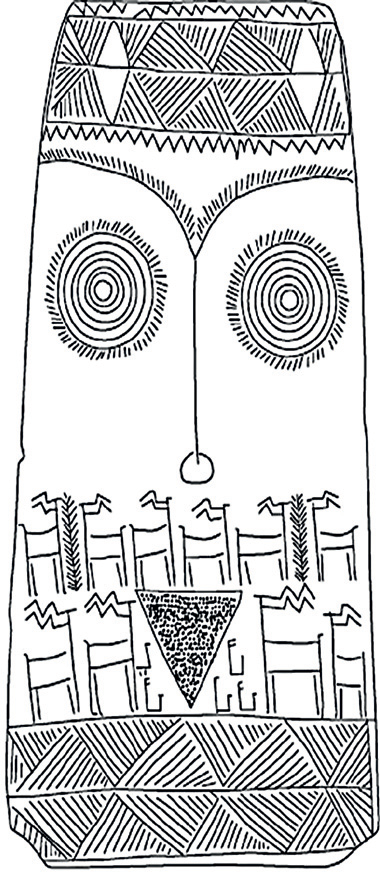

Photo Hendrik GommerIn the mentioned article, it is convincingly argued that many plaquettes feature owls. Large eyes, beak, area around the eyes, collar, and plumage have been used in drawings over the centuries to depict owls. The researchers compellingly demonstrate that these features are already used by young children. The merit of the research is as significant as, for example, the research by Serge Cassen in 2011, who showed that many alleged axes on menhirs were actually representations of sperm whales. (Cassen, Serge, Le Mané Lud en mouvement. Déroulé de signes dans un ouvrage néolithique de pierres dressées à Locmariaquer (Morbihan); Préhistoire Méditerranéennes 2011 https://journals.openedition.org/pm/582) (Megaliths, p. 103-112)

Sperm whale Mané-Lud: Photo Hendrik Gommer

Sperm whale Mané-Lud: Photo Hendrik GommerToys in graves

But the researchers go a step further. The prehistoric owls are carved in slate. Sand and polish the stone, and you can draw such an owl within 4 hours. Unlike moving megaliths, erecting menhirs, and making pottery, a child could easily do this. Moreover, the plaquettes were not trade goods because they are mainly found in Portugal and southern Spain, with Extremadura as the epicenter. It was not a luxury item but simply children's toys, the researchers conclude. Here, I found myself lighting the wick in the collar-necked bottle. In other words, it looks like children's toys, so it must have been children's toys.

But then why were so many plaquettes found in and around dome graves? The owl motif is also found on bones and even menhirs. Why the owl and not a deer or bear? These are also animals that appeal to children. These objections should have led the researchers to different conclusions: 'Agreed, clearly owls, but not children's toys.' Instead, these questions are dismissed too easily. The researchers write, 'The fact that many plaquettes have been found in burial contexts may suggest that they were once used as a tribute to the deceased. Offering plaquettes could therefore be part of a community ritual. This may also suggest that offering toys or dolls may have been a way in which younger members of the group participated in the burial rituals practiced by adults.' Toys that were later given to the deceased.

Eye idol

The theory of Juan J. Negro et al. sharply contrasts with that of archaeologists Estelle Orelle and Liora Kolska Horwitz (2015 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297676174_The_pre-iconography_iconography_and_iconology_of_a_sixth_to_fifth_millennium_BC_Near_Eastern_incised_bone). They tried to decipher the meaning of the eye idol, our owl, by comparing it with similar figures in the Middle East. In Neve-Yam, on the coast near Haifa in Israel, a bone with unique engravings from around 5500 BC was found. According to the researchers, the bone symbolizes a naked woman with large human eyes, eyelashes, eyebrows, stylized breasts, and a pubis. The similarity to the engraved bones in Los Millares is significant. In Los Millares, a bowl was also found with the eye motif on the front and deer on the back, with one of the deer having an enormous antler. This motif shows great similarities to a bone from Hagosherim (near the border with Lebanon). The bone also has large eyes, eyelashes, eyebrows, and a pubis, but in between is a deer with a tree or ear depicted.

Mari-stele: Drawing Estelle Orelle and Liora Kolska Horwitz

Mari-stele: Drawing Estelle Orelle and Liora Kolska Horwitz

The eye motifs also appear on the Mari stele from 3000 BC. The eyes are round, and with some effort, a beak can also be discerned. The resemblance to an owl's head is striking, but this stele was found in a temple in Syria, dedicated to the goddess Ninhursag. The connection of this fertility goddess with trees had become a clear element of the religion in the Middle East. In Syria and Assyria, these figurines probably served as fertility goddesses that people carried with them. But where are the deer and the pubis on the eye idols in Spain? And why do you never see the oval eyes that were common in the Middle East? These objections should have made Orelle and Horwitz think, but instead, they suggest that there was a slow shift from a female to a male deity. The pubis and eyelashes disappear, and the eyes become more penetrating. In the Middle East, around 3000 BC, the god Enki, the male god of wisdom and magic, appeared, who made the land fertile through rivers and irrigation. Orelle and Horwitz suspect that the eye idols in Spain, sometimes accompanied by zigzag lines (rivers or fields), may refer to such a deity.

Bird of death

While writing my book 'Megaliths, The origin of megalithic cultures in Europe,' I was impressed by the research of Orelle and Horwitz (Megaliths p. 247-252), until I read the research of Juan J. Negra et al. (Megaliths p. 236). At such a moment, there is a kind of crisis in your thoughts. Was it about images of gods or children's toys? It turned out that an overview of cultural expressions in one book can help gain a better understanding.

Tombe des Cazarils: Photo Hendrik Gommer

Tombe des Cazarils: Photo Hendrik Gommer

In the Tomb of Cazarils (Megaliths p. 295), built by the Fontbouissac culture between 2700 and 2300 BC, we find a menhir with clearly the same facial features: round eyes, area around the eyes, and a beak. But the menhir also has an arm. An owl with an arm. The menhir image has much in common with the menhir images made by the Treilles culture in South France around 3000 BC. Statue-menhir la Dame de Saint-Sernin (Megaliths, p. 293) is perhaps the most famous of them. The image has legs, a belt, arms, breasts, a collar, eyes..., whiskers, and a beak. Or is it a nose?

Statue-menhir la Dame de Saint-Sernin in Fenaille Museum, Rodez: Photo Hendrik Gommer

Statue-menhir la Dame de Saint-Sernin in Fenaille Museum, Rodez: Photo Hendrik GommerIn Sardinia, a rock tomb is decorated with spiral motifs (Megaliths, p. 326; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muIUPajOY_M). When I entered the tomb, I was greatly intrigued. It looks like a Corinthian column, but with the knowledge of today, it is a stylistic representation of an owl with a beak. A similar motif can be found in the Hagar Qim complex in Malta.

Ariete Domus de Janas: Photo Hendrik Gommer

Ariete Domus de Janas: Photo Hendrik GommerPieces of the puzzle are slowly falling into place. It is known that in Mesopotamia, the owl was considered a 'bird of the dead,' capable of carrying the soul of a deceased. What if, in the Neolithic era, people adopted a part of animism from hunter-gatherers? The belief that things and animals could be animated? And if they mixed this with the belief in the continued existence of ancestors? Did the owl symbolize the souls of ancestors? Because of its nocturnal life, silent wings, and large eyes, the owl is associated with death in numerous cultures around the world. It is not so strange that the owl appeared in dolmens and rock tombs. The menhir images then represented deceased ancestors, and the plaquettes were carried as a reminder of the ancestors. The combination of the owl's head with the anthropomorphic form confirms this thought. The deceased was still human but continued to live as an 'owl.' And later, with the rise of polytheism, the ancestral figurine transformed into a deity. Just as many Christians still wear a cross around their necks. They wanted to keep their ancestor, and later their god, as close as possible. This could be done with a plaque of an owl.

In Lepenski Vir on the Danube (Megaliths, p. 41-45), one of the oldest settlements in Europe, menhir images with fish heads were found. They were placed near graves. Lepenski Vir was initially a settlement of fishing hunter-gatherers and was later taken over by farmers where ancestor worship was more central. The fish heads have human features and always look sad, with the corners of the mouth turned downward. Did the fish head perhaps have the same function as the owl's head? Or did the hunter-gatherers feel guilty about the many killed fish and sought to repay the debt by sending the dead back to the fish? It is most likely that it was a combination of many feelings, as a symbol becomes more powerful the more emotion you can put into it.

Fish head from Lepenski Vir: Photo Hendrik Gommer

Fish head from Lepenski Vir: Photo Hendrik GommerWhile writing 'Megaliths,' I often wondered whether I was engaging in science or just weaving a story. Nowadays, you can clearly see where the latter can lead. Before you know it, you believe that people never landed on the moon. Yet, that is the essence of science, and therefore archaeology, I think. Creating a story, testing it against the facts, adjusting the story, retesting, etc. So that the story becomes stronger and stronger. In this sense, the collar-necked bottle as an oil lamp is a beautiful metaphor for scientific progress, and the owl for every debunked fantasy that ultimately leads to wisdom.

The photos are covered by the Creative Commons License.

Reacties

Note: HTML is not translated!