In June 2024, a Swedish research researchgroup (F.V. Seersholm et al., Repeated plaque infections across six generations of Neolithic Farmers) concluded that Neolithic farmers endured three plague epidemics during the period of 3300-2900 BC. They analyzed the DNA of 108 individuals from eight megalithic tombs, mainly near Falköping, Sweden (See also Megaliths. The Origin of Megalithic Cultures in Europe, pages 472-480). It was suggested that the third epidemic weakened the population to the extent that it halted the construction of megaliths in Europe. But is that the whole story? Why then did all indigenous men disappear around 2500 BC in southern England?

In Storstensgravar Rössberga, near Falköping, 156 individuals were found (Falbygdens Museum). Photo: Hendrik Gommer

The idea that epidemics caused the end of megalith construction in Europe stands alongside the theory that men were exterminated. Researchers from Harvard University (Olalde et al., The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years, 2019/ The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe, 2018) discovered that around 2500 BC, all Y chromosomes of the indigenous farming population in Spain and England were rapidly replaced by Y chromosomes from the Yamnaya, a steppe people from the east. From this, the researchers concluded that it was mainly men who were exterminated. Women largely survived. This marked the end of megalith construction, but the art of decorating pots continued thanks to the women who passed on the making of these 'bell beakers' to each other (see also Megaliths, pages 589-592).

Bell beaker. Museum für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Thüringens. Photo: Hendrik Gommer

There's no need to choose between these explanations. The plague epidemics undoubtedly weakened the population. In northern Europe, the Funnel Beaker culture from 3000 BC was displaced by the Corded Ware culture. The men of the Corded Ware culture had the Y chromosomes of the Yamnaya. The corded ware had unmistakable features of the funnel beakers. But in the rest of Europe, except for Southern Italy, the construction with large stones only ended around 2500 BC (see also Megaliths, pages 596-602). It is also noteworthy that it was mainly men who were exterminated. A disease cannot be responsible for that. Furthermore, the Swedish study showed that quite a few men had children with multiple women. This fits well with a situation where a large part of the men of a people were killed.

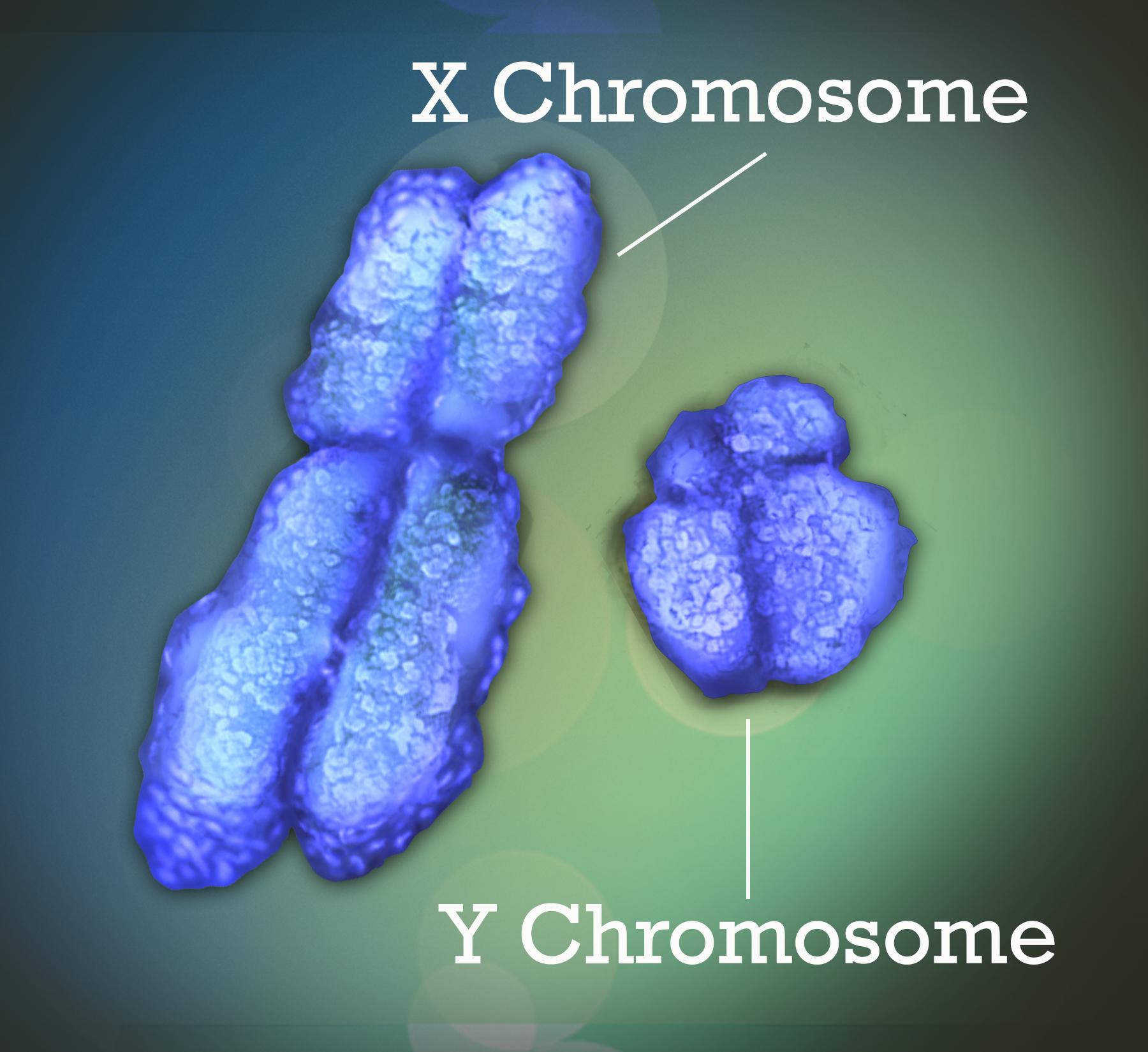

The role of the X and Y chromosome

Not surprising at all. Until today, wars are mainly fought by men, with subjugated women being abducted. They provide additional offspring for the conquerors. It's a very successful evolutionary strategy for the Y chromosome, the unique chromosome that only men possess. Men have an X and a Y chromosome, while women have two X chromosomes. Let's take a closer look at the Y chromosome.

X and Y chromosome. Photo: Jonathan Balley

During fertilization, genes from all chromosomes are mixed. This way, you get traits from both your father and your mother. For women, this also applies to the X chromosome. X chromosomes mix like other chromosomes. But this applies only to a limited extent to men's Y chromosomes. Certain parts of them do not mix with the X chromosome from the mother to prevent dilution of male traits. This could lead to infertility. Due to this lack of 'recombination', all men of a family have almost exactly the same genes on the Y chromosome. It's different for women. They share half of the genes on their X chromosomes, just like with the other 44 chromosomes. As a result, I, as a man, share the same Y chromosome as my brothers, cousins, father, grandfather, and all other men in the male line. So I know that the Hendrik Gommer who moved from Bentheim (Germany) to Schoonebeek (Netherlands) around 1600 not only had the same name as me but also the same Y chromosome. By the way, I seem to resemble him very little now, because after 11 generations, the other chromosomes have been completely mixed with my female ancestors. But the Y chromosome changes so little that I even share the same type of genes on my Y chromosome with apes. The number hasn't changed in 5 million years (J. F. Hughes et al. "Conservation of Y-linked genes during human evolution revealed by comparative sequencing in chimpanzee, 2005). However, the genes on the Y chromosome have a very high mutation rate. Because sperm cells have to multiply to millions, the chance of errors during gene copying is considerably greater than with the single egg cells produced by women. These mutations lead to differences between Y chromosomes (J.A. Graves JA "Sex chromosome specialization and degeneration in mammals", 2006). The differences between the Y chromosomes of men within a family are very small, even within a population they differ little, but the less the relationship, the more mutations come into play. Let's say the Y chromosome only has one hundredth of all the functional genes of a man. However, this does not mean that the influence of the Y chromosome is small. On the contrary, the genes of the Y chromosome affect the expression, the 'phenotype', of a large part of the other genes. A man and a woman who would have exactly the same genes and only differ with the Y chromosome would still be very different, physically and mentally. In other words, the Y chromosome not only determines how you look, but also guides your thoughts and feelings.

Why Y chromosomes benefit from war

One of these differences is important for the evolutionary explanation of the disappearance of the megalithic cultures, the cultures that built dolmens. We have already established that in women, their X chromosomes also mix. The daughter of a Neolithic farmer and a hunter-gatherer was rightly a perfect mix of both. But the son of the Neolithic farmer was primarily a Neolithic farmer, even though a large part of his genes were mixed. The evolutionary consequence was, and is, that it didn't matter whether a man passed on his Y chromosome himself or his brother, as long as it was passed on. The brother's Y chromosome could easily die off and still be successful through the survival of the other brother. Imagine four brothers going to battle against four other brothers. If only one brother survived, that one man would have eight women to pass on his Y chromosome to. More concretely, one Yamnaya man skilled with bow and arrow could easily kill four megalith builders from a distance (see also Megaliths, page 589). He would then take the women and thus spread his Y chromosome rapidly via the sons he sired with these women. This pace could further increase if the dolmen builders were weakened by epidemics. Not only the women, but also the settlements and other facilities could then be taken over and used to spread the own Y chromosome. As a result, within a few generations, the Y chromosome of male megalith builders was replaced by the Y chromosome of the Yamnaya men. Because the men of both cultures had been separated for a long time, 3000-5000 years, numerous mutations had occurred. The Y chromosomes of both peoples had therefore started to differ. The dolmen builder variant thus died out. The best adapted Y chromosome survived.

Arm guards for ber culture. Museum für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Thüringens. Photo: Hendrik Gommer

Why X chromosomes prefer to wait for the outcome

And what about the X chromosomes of women, what is their evolutionary strategy? Their genes are mixed in every generation. For female genes, it doesn't matter with which man they reproduce, as long as the man takes care of them and the offspring. It's no coincidence that power is eroticizing. It is therefore likely that after some generations, the women of the farmers resigned themselves to the conquest by the Yamnaya men. After several generations, they had forgotten the genocide, especially since they were married off to a different village each time. Thus, they grew up with the family's legacy of the man. For the X chromosome, the main strategy is to ensure that itself and the immediate offspring survive. After all, it only shares half of the genes on the X chromosome with a sister, and only ¼ of the genes with a grandmother and 1/8 with a niece. X chromosomes of women who find themselves in bad conditions, such as famine, are therefore benefited by war, but not by fighting it out. The strategy that women receive through their X chromosome is 'ensure survival', while men follow the strategy dictated by the Y chromosome: 'ensure that you or your brothers win'. This strategy is also confirmed by the fact that some women in the Neolithic era were found to have a mix of genes from different peoples. In the Swedish study, for example, a mix of genes from the Pitted Ware culture (also Megaliths, pages 450-451) and the Funnel Beaker culture (Megaliths, pages 440 ff.) was found in two women.

The Emergence of a New Culture

Thus, the mystery of the disappearance of the megalithic cultures has been solved. The men who had the skills to erect large stone monuments were weakened by the plague epidemics that ravaged the Neolithic period. As their numbers dwindled, they were increasingly unable to defend themselves against the warriors from the east, who wielded horses and bows. Gradually, they became outnumbered and were, within a few generations, displaced by the mound-building Yamnaya (Megaliths, p. 590 ff.). The Y chromosome of the original population was completely eradicated, and with it, the knowledge of constructing megalithic monuments quickly disappeared. However, their women continued to produce funnel-shaped pottery, a craft they further developed into bell-shaped pottery. The daughters of the farmers continued to pass on their genes, leading to the mingling of the remaining genetic material of the megalith builders with that of the Yamnaya (Megaliths, pp. 590-591).

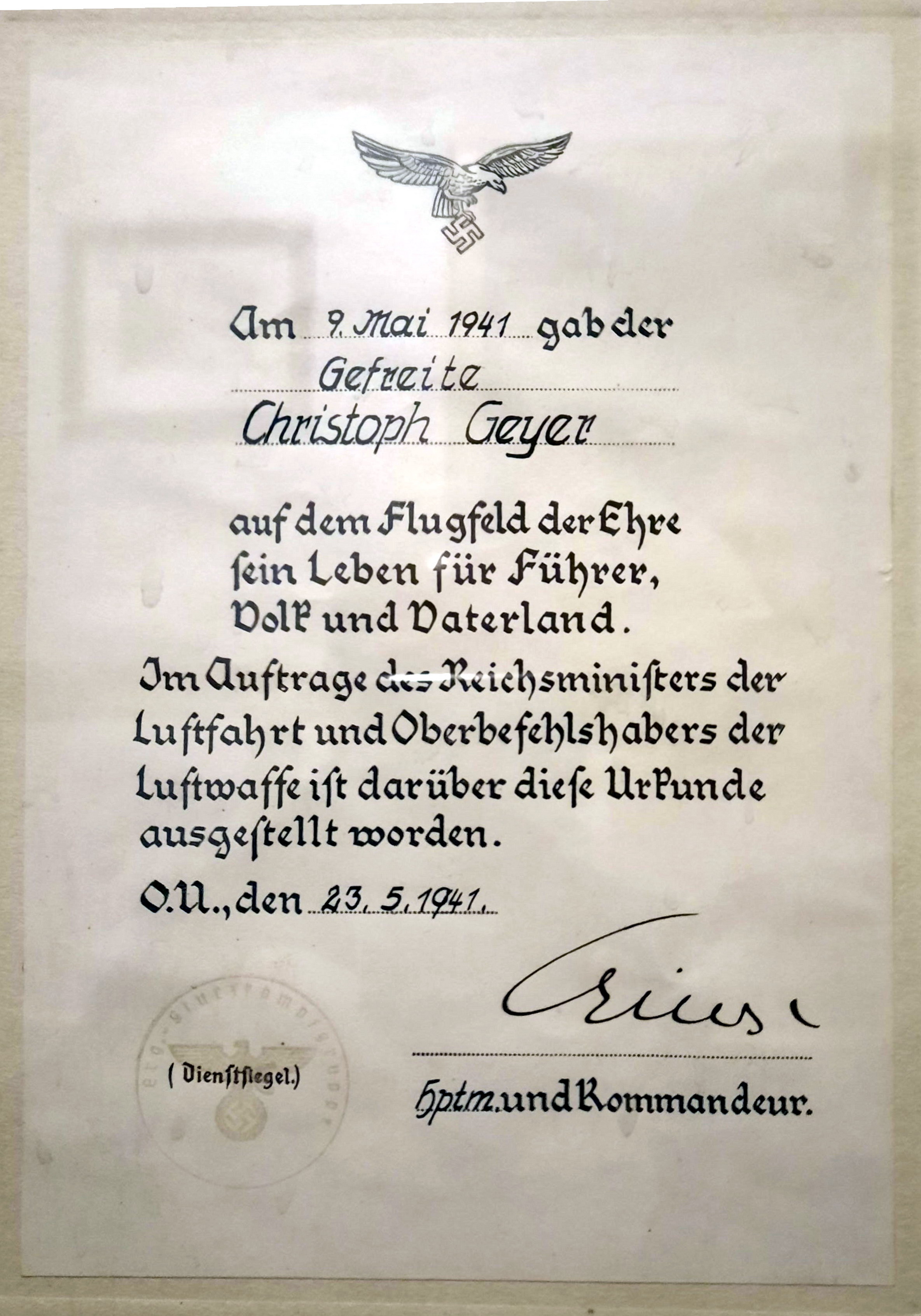

For people and fatherland. Public Domain.

The Winner Takes It All

This explanation also sheds light on why it is generally men who ‘fearlessly’ go to war. It’s literally in their DNA, largely dominated by their Y chromosome. Although biology ensures a high degree of diversity, it is generally the case that a male individual feels subordinate to his family, his group, and his fatherland. As long as the men of his own people—who share the same Y chromosome—prevail, he too emerges victorious. This inherent drive makes it relatively easy to convince men that they should sacrifice their lives for the ‘fatherland.’ It is a cultural translation of what the Y chromosome dictates: you must give your life for the survival of your Y chromosome, because the winning Y chromosome ‘takes it all’—the women, the resources, and the land. Dictators, populism, and social media have become adept at exploiting these biological drives. This principle is so deeply ingrained in male DNA that war—and racial conflicts—will always remain a possibility, unless it is 100% certain (and not a percentage less) that the war cannot be won. This is where our modern era differs from the Stone Age. Nowadays, wars can no longer be won, but try explaining that to the Y-chromosome.

Reacties

Note: HTML is not translated!